| The Information Triad: A model of past, current and future information technology utilization in the firmby Marc Demarest, |

The present explosion of information technology and of microelectronics is much more closely

related to the functioning of society as a whole than was the Industrial Revolution. To a much

greater extent than other technologies, microelectronics affects the very essence of social

cohesion, i.e., communication. Information and communication constitute the fabric of society in

more than a metaphoric sense, They do not remain unaffected when communication processes

are mediated, channeled and partly taken over by technology.

The Club of Rome Report on Microelectronics and Society (1982)

The first language that emerges from the process of scientific clarification is in theoretical physics

usually a mathematical language, the mathematical scheme, which allows one to predict the

results of experiments. But [the physicist] has to speak about his results also to non-physicists

who will not be satisfied unless some explanation is given in plain language, understandable to

anybody. Even for the physicist the description in plain language will be a criterion of the degree

of understanding that has been reached. To what extent is such a description at all possible?

Werner Heisenberg, “Language And Reality in Modern Physics” (1958)

Abstract

The adoption and utilization of information technology (IT) in the modern commercial firm, when viewed from an appropriate distance, has occurred in a fairly regular way, across firms, industries and geographical areas. The pattern revealed when we take a broad, schematic view of how IT has penetrated commercial environments can tell us a good deal about where we are headed.

Introduction

The primary problem of information technology today is our inability to speak about its workings, its motives and its benefits in a way that is intelligible and relevant to commerce. The language of baud, byte and bandwidth is, as the philosopher Richard Rorty would put it, incommensurate with the language of the balance sheet and the board room.

This is due, for the most part, to the absence of:

- a crisp, plain-speaking model of information technology in the abstract -- what is IT and what can IT be used for?

- an equally crisp history of the uses of information technology in the firm historically -- where did IT come from and how have we used it?

- a model that allows business and technology to speculate together, in plain language, about the future uses of information technology within the firm, the problems and challenges associated with those future uses, and the decisions to be taken, today and in future.

In this essay, we draw on the resonances of a simple model -- the Information Triad [see note 1] -- to provide these missing elements. Our objective is to offer business and IT a common model for understanding where they have been together, where they are now together and what, in future, they will have to do together in order to survive and thrive in the destabilized world economy of the twenty-first century.

The Information Triad in the Abstract

In the abstract, the Information Triad captures a simple, fundamental insight about the limits of information technology now and in the near future. Put succinctly, all information technology does or can do for firms and individuals today is:

- capture and store data

- distribute data for consumption and analysis, to produce information

- connect people together into collaborative working environments where information is shared to produce knowledge.

Those three vectors form the essential IT triad.

The legs of the triad imply some historical precedence, inasmuch as we built, and are building them, in order.

The Prehistory of Information Technology in the Firm

For firms of more than 30 years standing [see 2], it is highly probable that information technology entered the firm through the accounting department, the vice-president of finance and the firm’s audit partner. The first computers, after all, had been built to deal with particular complex problems of calculation, having to do with census data, and audit firms were quick to realize that the computer offered firms -- particularly publicly-traded regulated firms -- a way to:

- increase the accuracy of accounting and finance functions

- reduce the time required to complete formal reportage requirements and to close months, quarters and years

- reduce the number of people required to perform those tasks.

The use of IT was in short justified in both its target -- the counting of money -- and its use -- the saving of money.

IT was in short the exact analog of the mechanical and electromechanical technologies that proceeded it: firmly in line with the Tayloresque agenda of more and better work from fewer people. IT was fundamentally about cost reduction, and -- far from being a strategic element -- was a tactical convenience of a firm that was always doing something other than IT and which based its performance on something other than information.

The First Wave: Transaction Processing

Once information technology had demonstrated its usefulness in accountancy, it began to be applied to money-counting and ultimately product-making and product-moving problems across the firm. IT became “transaction processing,” first batch-oriented, and, later, as the pace of the economy increased, online transaction processing (OLTP), which is how we understand this leg of the Triad today.

This first wave of IT usage dominated the firm’s model of how IT could be used from the 1960s until roughly 1980, and had a number of deep, salient characteristics worth enumerating.

These technical characteristics were in turn a reflection of some fundamental business assumptions that drove IT into its role in the firm, and focused IT at particular targets with particular objectives.

In the final analysis, the transaction processing leg of the triad:

- focused on the tasks of individual production workers

- regiments, controls and deskills that work

- in the interest of cost containment, variance elimination, and increased efficiency

- based on the premises that the risk to capital warrants both the deskilling and the accumulation of data, and that the internal efficiency of the firm is the primary guarantor of market success.

The Second Wave: Decision Support

Beginning in about 1985, the average firm began to realize two things:

- its quest for the automation of transaction processing was nearing completion, or, at the very least, that the Pareto effect had set in

- the accumulation of data did not in fact alleviate the risk to capital, which was in any case no longer the primary risk from a strategic perspective

At this point, firms began to take the first tentative steps down the second leg of the Triad: the leg we refer to as decision support. Now it is true that firms had, since the early 1970s, decision support capabilities, in the form of MIS and EIS systems, but these systems were flawed in conception in at least two regards:

- they assumed decision-making (or interesting decision-making at least) occurred in the central corporate regime, rather than in the peripheral business team environment

- they assumed the kinds of analyses performed on operational data were uniform -- that in effect the world was stable, and all firms instrumented themselves in the same basic fashion.

In fact, neither was true. The important decisions, it turns out, were being made all the time everywhere, and the kinds of analyses being performed were highly idiosyncratic and in a more or less constant state of flux. MIS and EIS were overturned, by 1990 or so, in favor of a new model of information distribution and analysis: client/server DSS targeted at the knowledge workers.

The fundamental shift we need to mark here is the shift from data -- the sine qua non of the first leg of the Triad -- to information, placed on the desktops of knowledge workers for analysis and action. This shift exhibited itself as indicated in the chart below.

And there were of course similar underlying shifts in the business model, shifts that both forced and supported the decline of transaction processing and the rise of decision support as the dominant focus within firms.

The decision support leg of the triad:

- focused on the decisions of individual knowledge workers

- supports and enables that work

- in the interest of management-by-fact, and tactical revenue-enhancement opportunities

- based on the premises that the risk of incomplete information warrants the recentering of the knowledge worker and the desktop in the enterprise, even though both are fundamentally destabilizing.

The Third Wave: Business Communications

Early adopter firms that made the transition from the first to the second leg of the Triad in the early 80s made, in the late 80s, a crucial discovery -- knowledge workers are gregarious. They are relentless chatterers and scribblers, and their capabilities are amplified by two kinds of networks:

- a more or less formal network of supplier-consumer relationships among knowledge and production workers embodied in the firm’s (often informal) business processes

- a very informal, cross-functional, cross-process network of contacts and associations among workers in and across firms. Both of these affiliational structures, it turned out, needed to be supported explicitly by IT for the decision-making process enabled by the decision support vector to actually result in effective decision-making and execution on taken decisions.

Hence the third leg of the triad -- business communications -- which focuses on providing the infrastructure and agency to connect people, electronically, to other people across time, space and organizational regime. Electronic messaging, use of collaborative work environments like Notes and the World Wide Web, even desktop video conferencing -- all these technologies focus on the relationships among people, a model in which data-become-information is transformed, through collaboration, into actionable stuff: into knowledge. Like the vectors before it, business communication once again modified the core technical characteristics of the firm’s IT focus.

And, once again, changes in these technical characteristics were driven by changes in the underlying strategic management regime.

This leg of the triad introduces more fundamental changes in the conceptual models of IT than either of the two previous vectors. Business communications:

- focused on the collaborative behavior of networks and business teams

- facilitates that collaboration and those networks

- in the interest of knowledge development and marketplace action based on knowledge developed by teams

- based on the premises that the increased process-orientation and value-chain orientation of the marketplace must be mirrored and supported by IT.

The Transition Points

Each leg of the Triad, we can see, represents the dominance of a particular way of thinking about the design center of IT projects.

- The first leg, transaction processing, focused on routinizing the tasks of the individual production worker in the name of deskilling and rendering more efficient that worker.

- The second leg of the Triad, decision support, focuses on enabling the decision-making of the individual knowledge worker in the name of empowering and rendering more effective that worker.

- The third leg, Business Communications, focuses on interconnecting all the employees of the firm, as well as employees in the firm’s suppliers, downstream channel partners and customers, all in the name of facilitating their closer collaboration.

The shifts at the transition points are instructive, most importantly because they tell us something about the future: the next sets of transitions we will encounter.

Transition point 1 was essentially the decision to use IT to deskill and routinize production work. This was a fairly conventional transition, and did not fundamentally disrupt the firm’s culture or organization, since in most cases this production work was already culturally devalued by the firm. The essential drivers for this change were (a) the availability of a solid-state-based technology that promised to do for the “white collar factory” what mechanical and electro-mechanical technology had done for the shop floor, and (b) compelling existence proofs of the cost-reduction and cycle-time benefits of IT applied in this fashion (the accountancy function).

Transition 2 was significantly more disruptive. The fundamental decision was to open the data vaults and turn data over to the people who actually made the salient business decisions for the firm. The change was heralded, if not catalyzed, by two important drivers: the personal computer, and the design center for the personal computer, the knowledge worker. In the same way that a previous generation of white collar workers depended on calculators, typewriters and telephones to do their work, knowledge workers after 1988 or so were dependent on the availability of personal computers, and personal productivity tools (most particularly the spreadsheet and the word processor) to produce their intellectual property.

But Transition 2 did not disrupt some of the fundamental assumptions of Transition 1: specifically, the focus of IT was still the orchestration of the tasks of individuals. The individual changed -- from a production worker to a knowledge worker -- and the type of task changed: from making and moving things, from data entry associated with making and moving things, to taking and making decisions. And, if the guild of knowledge work had not been one in which the inspection and rationalization of work processes violated the fundamental unspoken contract between the knowledge worker and the firm, I believe we might have tried to routinize and automate that class of task as well.

It is Transition 3 that finally breaks the orchestration model that focuses on individuals and tasks. Driven in this case by (a) process-oriented management disciplines like TQM and BPR and (b) the attendant cultural emphasis on teaming, connectedness and asynchronous work, Transition 3 breaks open the whole concept of IT-as-orchestration by focusing IT on connecting collaborators, not on managing the output (in the case of OLTP) or the input (in the case of DSS) of the tasks of individuals. Transition 3 creates an infrastructure that is nearly purely facilitative. Everyone is connected to everyone else, and what passes along those electronic connections is, by the time Transition 3 is complete, inscrutable to the firm: outside the pale of IT.

And that -- the idea that the firm provides facilitative technology for the production of knowledge from information from data, but cannot scrutinize either the work product or the means of production -- quickly becomes untenable for strategically-minded firms aware that their competitive advantage derives from their process innovation and their intellectual property.

Transcending the Triad: Enterprise Workflow

In other words, the model implies some cyclicality. Once we have ‘completed’ the business communications regime, we are right back where we started, at the fundamental question IT was brought into the firm to address: how to make rational, inspectable and more efficient the work of employees, and thereby increase the production of economic value for the firm, its customers and its owners. There is, it appears, a fourth transition point. But what is it?

We refer to this transition as the transition to enterprise workflow: to the use of the infrastructure created by the triad to create a set of enterprise-wide applications that embody process logic, expose knowledge work to scrutiny and instrumentation, and explicitly orchestrate the tasks inside the firm’s components of the value chain.

Enterprise workflow is the management of commitments: within the firm, between the firm and suppliers, between the firm and channel partners, between the firm and customers. Enterprise workflow cannot come into existence until the Triad is complete and functional.

We have talked elsewhere about the strategic dilemma inherent in enterprise workflow -- the empowerment versus control paradigm that requires us to ask ourselves whether the firm ought -- from an ethical perspective -- to use workflow as a deskilling or a liberating technology model. Drucker’s typology of knowledge work is illustrative in this regard.

What Drucker argues, in this analogy, is that highly-innovative business teams’ processes need to be scored and handed down to progressively more closely-managed teams as the value inherent in the process or its output decreases. Implicit in his model is the notion that such a “devolution” (supported by technology) is fundamentally enabling, since:

- it frees jazz combos for perpetual creativity, exploration and innovation

- increasingly, orchestras and cover bands are outside contractors to the firm.

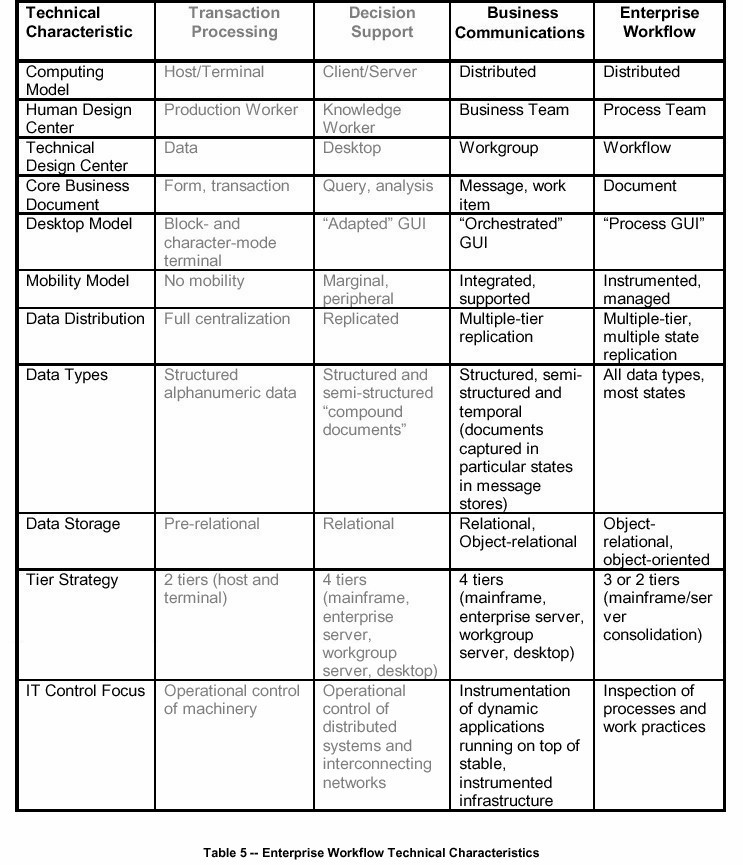

We can sketch the outlines of the technical characteristics of the enterprise workflow paradigm as follows:

We can speculate on the business drivers for these changes.

But in the final analysis, we know too little about the sociocultural context in which this paradigm comes to dominate IT application within the firm to be sure exactly how it manifests itself. Breaking open the guild of knowledge work is a problematic cultural and ethical issue, on which far too little theoretical work has been done.

Beyond The Firm’s Boundaries: Electronic Commerce

But, to continue the speculation, suppose a firm with a fully-capable enterprise workflow IT infrastructure. What would such a firm do next? We do know the answer to this question: participate in the automation of the remainder of the value chain, and beyond that, create the capability for instantaneous, late-binding value chain creation. After enterprise workflow, in other words, comes electronic commerce: the IT-enabled ability for a design center firm to orchestration the on-the-fly construction of a largely electronic value chain to make, market and sell a product or service to a possibly fleeting, possibly instantaneous marketplace.

There are two things worth noting about this speculation:

- it appears that technology will facilitate the simultaneous arrival of enterprise workflow and electronic commerce -- firms will be struggling to rationalize their internal value chain at the same time they are forced or led to participate in early electronic value systems or supply chains.

- at one level, all this paradigm does is change the definition of the word enterprise, from “firm” (as it is in enterprise workflow) to “supply chain” as it is in electronic commerce.

The State of the Firm Today

So, assuming we are more or less accurate in our historical assessment and projections, the question arises: where are we exactly? In what state is the typical firm’s Information Triad?

In our experience, the typical firm is:

- 80% complete in transaction processing

- 25%-40% complete in decision support

- about 15% complete in business communications.

In the case of transaction processing, the following are generally the case:

- the firm is capturing almost all the data it can capture as efficiently as it can capture it

- the remaining data required does not belong to and cannot be generated by the firm; it is external data held by proto-data syndicates, regulatory bodies or the market at large

- a few critical strategic transaction processing application opportunities exist in most firms: new applications that require new development technologies and methodologies

- some firms, unaware of the Triad, are reengineering their existing, functional OLTP applications instead of migrating to the second leg of the triad.

In the case of decision support, most firms are doing little more than dumping (in many cases dirty and incomplete) data sets on the desktops of knowledge workers for analysis. What remains to be done in this leg of the triad?

- completion and cleansing of the decisional data

- explicit support for the decision making process -- structuring, analysis, and option selection

- explicit support for the propagation, monitoring and evaluation of taken decisions.

In the case of business communications, little exists in the typical firm beyond isolated, unconnected electronic mail domains. External connectivity, message-enabled applications, collaborative work environments, knowledge management systems -- all remain to be constructed.

Conclusion: The Gap, The Bridge, The Common Language

Our task is therefore clear: to use the technology to support the unstructured activities (of

knowledge workers) and to bind together structured and unstructured work. The barrier lies in the

fact that, although the role, capability and justification of IT systems have changed enormously

in twenty years, the architecture of data processing has stayed resolutely wedded to the support

of transaction processing capability. That replaced computational capability as the core of IT in

the 1960s and 1970s, justified by cost savings that, despite all the groans from users, were often

gigantic.

But over the 1970s and into the 1980s, database management and networks have become the

dominant capabilities -- and they demand an architecture that lends itself to the support of

unstructured activities and thinking roles within an organization.

Robert Heller, Culture Shock: The Office Revolution (1990).

The organization of the post-capitalist society of organizations is a destabilizer. Because its

function is to put knowledge to work -- on tools, processes and products; on work; on knowledge

itself -- it

must be organized for constant change....It must be organized for systematic abandonment of the

customary, the familiar and the comfortable -- whether products, services or processes, human

and social relationships, or the skills of the organizations themselves. It is the very nature of

knowledge that it changes fast, and today’s certainties will be tomorrow’s absurdities....Every

organization has to build into its very structure the management of change.

Peter Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society (1993).

As technology transforms the logic of competition, technology disappears as a source of

sustainable competitive advantage. As what has happened in steel and other manufacturing

segments happens everywhere, and more and more companies enter the information economy,

the ability of any particular company to master the new technologies ceases to confer any

particular competitive advantage. Instead, technology drives the logic of the new economy to the

next step -- to people, the knowledge workers, whose skills, abilities and commitment will

ultimately determine whether a company can be successful.

Alan Webber, editor, Fast Company

The search for a model and a language to bridge the gap between IT professionals and their business counterparts is nothing new. Since at least the late sixties, we have seen, regularly, the release of methodologies, models and formulae that promised to produce “a common language” for business and IT, a common language that was usually neither precisely the language of IT nor precisely the language of business.

Such efforts strike one as analogous to Esperanto: a language no one speaks as a native is no language at all. The common language of IT and the business is the language of the marketplace, the language of commerce, the language of the balance sheet and the board room. IT professionals may feel allegiance to a IT guild practice first and the firms they work for second, but this is not the necessary state of affairs. It is in fact the product of where and what we have been, together. What we need to transcend the gap, rather than bridging it, is common cause.

What builds common cause is, first and foremost, common history. We believe the history encapsulated in the Information Triad is that common history, and also therefore that common cause.

The quid pro quo for the IT organization is the transition from technologist to business analyst, translating business objectives for a small group of aligned vendors who take on an increasing share of the work formerly done in house as in-house personnel become experts in translating business requirements -- strategic and tactical -- into specific technology requirements within an overall enterprise IT architecture owned by the firm and maintained by the IT organization. In short, a new and valued role.

The quid pro quo for the business is stable, versatile infrastructure, supporting rapid reengineering of business processes increasingly supported and facilitated by software. In short, what the firm needs to compete and win.

Ultimately, as Alan Webber is fond of saying, the soft stuff is the hard stuff. The technology is social, knowledge destabilizes and people are the source of durable competitive advantage. We are in soft space, for the forseeable future.

Completing the triad, bringing enterprise workflow into being, and shepherding the firm into the era of electronic commerce rests on our abilities to intervene now, do the required enterprise architectural planning, and to move forward with a model of the business in which IT is a strategically-integrated, enabling component: in which “we” are the business including its customers, “they” are the competition, and “they” are in danger.

Notes

[1] The term Inf ormation Triad and its visual representation are the copyrighted property of Sequent Computer Systems, Inc. Copyright © 1994 by Sequent Computer Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

[2] In my experience, newer firms often introduced information technology elsewhere first, because these firms were --as it were -- jumping onto the path represented by the Triad in mid-phase, and were simply reflecting the focus of their compatriots at the time. Firms first entering a hard goods market in the early 1980s were more likely to invest in MRP and factory automation than elsewhere, because that was the center of the transaction processing marketplace at that time.

About the Author

Marc Demarest is the CEO of Noumenal, Inc., a private consultancy focused on business turn-around and go-to-market services for intellectual property-based companies in technical and commercial markets. Prior to Noumenal, Marc was Chairman and CEO of DecisionPoint Applications, Inc., the industry's leading provider of packaged data warehousing software for financial, human resources, manufacturing and distribution analysis. Marc has also held executive positions with The Sales Consultancy, Inc., a high-technology sales and marketing consulting firm based in Dallas, Texas and the United Kingdom, and Sequent Computer Systems, Inc. in Portland, Oregon, where he led the development of worldwide sales and marketing process development and created an APQC award-winning knowledge management technology environment. Widely known as the father of data marting, Marc publishes and speaks regularly on topics ranging from knowledge management and decision support systems to IT technology futures and information ethics. He holds BA degrees in Political Science and English Literature from Bucknell University in Lewisburg, PA., an MA from the University of South Carolina, and is a graduate of the Stanford Institute's high-technology business management program.

Citation

Demarest, M., "The Information Triad: A Model Of Past, Current And Future Information Technology Utilization In The Firm", DSSResources.COM, 06/29/2007.

Marc Demarest provided permission to archive articles from the Noumenal website at DSSResources.COM on Friday, December 5, 2003 and he provided permission to archive and feature this article. This article is at Noumenal URL http://www.noumenal.com/marc/triad1.pdf. This article was posted at DSSResources.COM on June 29, 2007. Copyright © 1994-1995 by DP Applications, Inc.